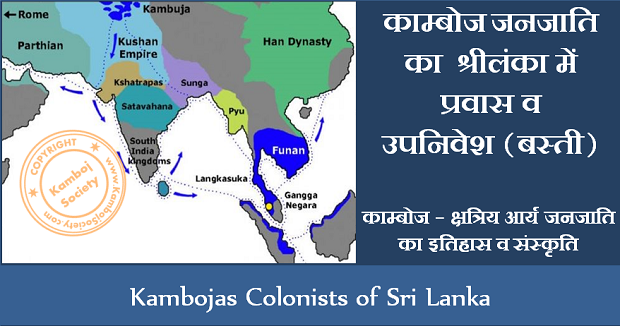

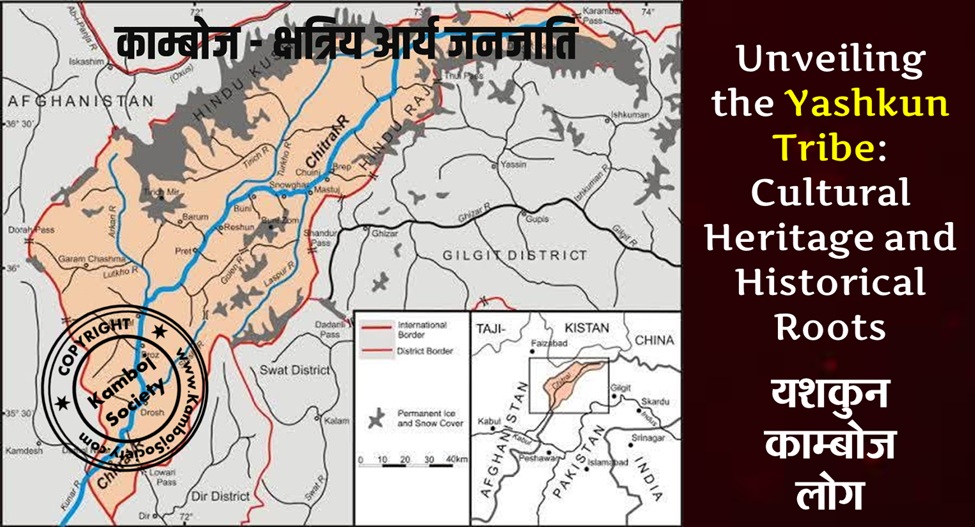

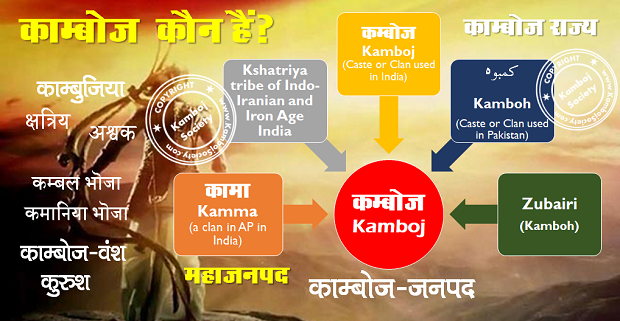

'Lanka' in Sanskrit means 'island.' Many ancient Indian Sanskrit and Pali texts refer to this island as Sinhala or Simhaladvipa. The Arab and the Portuguese traders corrupted the name to Seilan, Ceylon, Ceilão, etc. In English, the name is written as Sinhalese or Singhalese. The Sinhala also refers to about 74% of the population speaking the Sinhala language which belongs to the Indo-Aryan family and is closely allied to Sanskrit, Pali and Prakrit. The earliest colonists of Sri Lanka migrated from northern India but controversy exists as to the provenance of these early colonists; the traditions contain evidence for both the northwestern and the northeastern parts of the Indo-Gangetic plain. The first colonists probably hailed from the Saurashtra in Gujarat. Their ancestors are believed to have migrated earlier from Sinhapura of upper Indus near Kamboja/Gandhara region to the Saurashtra peninsula in Gujarat via lower Indus. Before arriving in Sri Lanka, these earliest known colonists called at Soparaka on the west coast of India and landed in Sri Lanka at Tambapanni, near Puttalam on the day of Parinibhana ("decease") of the Buddha (542 BCE or 486 BCE). SOME INSCRIPTIONAL REFERENCES TO ANCIENT KAMBOJAS IN ANCIENT SRI LANKA....THE MOST REFERENCED ETHNIC COMMUNITY IN THE SINHALESE INSCRIPTIONS BELONGING TO THIRD/SECOND CENTURY BCE [1] no. 622: 'Gamika-Kabojhaha lene' The cave of the village-councillor Kamboja; Paranavitana, 1970: [2] no. 623: 'Gamika-Siaa-putra gamika-Kabojhaha lene' The cave of the village-councillor Kamboja, son of the village-councillor Siva' Paranavitana, 1970: [3] (no. 625) (1) 'Cam ika-Siua-putra gamika-Kambojhaha jhitaya upasika-Sumanaya lene.' The cave of the female laydevotee Sumana, daughter of the village-councillor Kamboja. Dr. S. Paranavitana, 1970 [4](no 625) (2) 'gamika Kabojhaha ca sava-satasoyesamage pati' The cave of the son of the village-councillor Siva. May there be the attainment of the Path of Beatitude for the village-councillor Kamboja and for all beings. 75 J. Bloch, 0950: 103, 130), ... Dr. S. Paranavitana, 1970 [5](no. 553): 'Kabojhiya-mahapugiyana Manapadaiane agataanagat-catu-disa-agaia' [The cave] Manapadassana of the members of the Great Corporations of Kambojiyas, [is dedicated] to the Saiügha of the four quarters, present and absent. Dr. S. Paranavitana, 1970 [6] (no. 990): 'Gota-Kabojhi(ya]na parumaka-Gopalaha bariya upasika-Citaya lepe iagaio' The cave of the female lay-devotee Citta, wife of Gopala, the chief of the incorporated Kambojiyas, [is dedicated] to the Saiügha. Dr. S. Paranavitana, 1970 [7] Mediaval age inscription, refering a KAMBOJA VASSALA (i.e Kamboja Dawara/or Kamboja gate) found from Polonnaruva near Vishnu temple. Discovered in 1887 by S. M. Burros. (Ref: Journal of Ceylone B Branch of Royal Asiatic Society., Vol X., X No 34, 1887, pp64-67). [8] Mediaval age inscription (1187-1193 AD), found from Ruvanveli Dagba, Anaradhapura in Sri Lanka. It refers to Kambojdin people, which is modified version of Kamboja. (Ref: Don Martino de Zilva Wickeremsinghe, Epigraphicia Zeylanka, Vol II., Part I & II., p 70-83; Rhys David, J.R.A.S. Vol VII., p 187, p 353f; Muller. E. AIC., No 145; J.R.A.S., Vol XV., 1914, pp 170-71). See below the wording of this inscription written in Sinhali belended with Sanskrit. 'Nuvarata hatapsina sata gavaka pamanah tana haam satuna no narye hakhye abhaya di ber lava dolos meh va tana masuta abhaya de Kambojdin ran pili aadibhu kamati vastu de paksheen no badan niyayen samata kota abhaya dee' See original text in the reference quoted below or in Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 354, Dr J. L. Kamboj). (Epigraphia Zeylanka Vol II., p 80). THE GRAMANIS OF THE WEST-INDUS MAY HAVE BEEN THE ANCESTORS OF MAJORITY OF SINHALESE POPULATION. Not only the Brahmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka refer to the guilds/Sanghas/corporations (Puka/Pugas, Gote/Goshata) among Sri Lankan Kambojas but also they refewre to their republican titles like Gamika (=Gamini=Gramani) and Paramaka (Parmuka/Parmukha i.e chief of the Sanghas). The Gramani as a royal title is not referred to in ancient Sanskrit literature. However, Gramani as a Puga/Sangha term is referred to in Panini's Ashtadhyayi. Also MBH makes references to Gramani people/Sangha located in west of river Indus. One Gramani group had organised themselves into a Puga (Sangha) and are referenced to have been living on west of Indus, first in Upper Indus and then the lower Indus, from where they appear to have moved to Gujarat/Surashtra and then finally some section of them onto Sri Lanka. The ethnic connections of these republican Gramaney people are not mentioned anywhere. Mahabharata refers to the fight of Nakula with these powerful Gramanis living on the banks of lower Indus in western India.

- Sanskrit:

- gananutsava sanketanvyajayatpurusharshabha .

- sindhukulashrita ye cha gramaneya mahabalah .//8.

- ” (MBH 2/32/9)

KAMBOJAS IN SRI LANKA: OPINIONS FROM SOME SCHOLARS

David Parkin, and Ruth Barnes

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE ON SHIPPING COMMUNITIES page 108/109 " The second category of beads which deserves attention, is those made from lapis lazuli, becamee the only known source for this material in antiquity was Badakhshan (in northern Afghanwestan). The author of the Periplus mentions lapis lazuli among the products exported from Barbaricum.72 This precious material doubtless travelled along the sea route to reach the southern coast of Sri Lanka. Hema Ratnayake (1993: 8Q.) has also observed that on a painted slab belonging to one of the frontispieces of the Jetavana stupa, there are traces of lapis lazuli underneath the line of geese. He dates it to the third century AD, to the reign of king Mahasena, who built this feature of the stupa. The intaglio depicting a seated wild boar, unearthed along with carnelian seals and beads from Akurugoda (Tissamaharama) on the southern coast of the island, is important in this context. . This type of wild boar is known on Sasanian intaglios.73 The presence of lapis lazuli on the southern coast of Sri Lanka cannot be an isolated event, because epigraphical evidence bears witness to the fact that this area had close relationships with the regions of Afghanistan. 'Kaboja' occurs as a proper name in three inscriptions from Koravakgala (Situlpavua) in the Hambantota District, on the southeastern part of the island, in ancient Rohana.74 S. Paranavitana (1970: xc) believed that the Kabojha, Kabojhiya and Kabojhika are to be connected with the ethnic name Kamboja, which occurrs in Sanskrit and Pali literature as well as in the Vth and Xlllth inscriptions of Asoka, Kabojhiya being equivalent to the derivative term Kambojiya and Kabojika to Kambojika.75 The Brahmi inscription from Bovattegala on the southern border of the Ampari District, a few miles from the northeast limit of the Hambantota District, also in ancient Rohana, refers to 'Kabojhiya-mahapugyiana' i.e.'those who were members of the great corporation of the 'Kabojhivas'.76 The Brahmi inscription from Kaduruvava in the Kurunagala District, to the southwest of Anuradhapura, mentions a parumaka (Chief) of the Gota-Kabojikana, i.e. of the corporation of the Kabojikas.77 These inscriptions indicate that the Kambojas had organised themselves into a corporations and were certainly engaged in trade. The Sihalavatthu, a Pali text of about the fourth century (on page 109) attests that a group of people called the Kambojas were in Rohana. In the third story of this text, called Metteyya-vatthu, we are informed that the Elder named Maleyya was residing in Kamboja-gama, in the province (janapada) of Rohana on the Island of Tambapanni.78 The Kambojas are often mentioned together with Yonas (Yavanas), Gandharas and Sakas. The Kambojas were a native population of Arachosia in the extreme west of the Mauryan empire, speaking a language of Iranian origin.79 The finds on the southern coast of the island of lapis lazuli from northern Afghanistan and various coins of Soter Megas, Kanishka II, Vasudeva II and posthumous Hermaios, all from Bactria and Northwest India, and the references to the Kambojas of Arachosia, compel us to believe that there were close relationships between Sri Lanka and the communities of Central Asia and North-West India. S. Paranavitana (1970: xci) did not exclude the possibility of the presence of Sakas in the island. His starting point was the inscription in Brahmi script, known as Anuradhapura Rock Ridge West of Lainkarama,so which refers to 'The flight of steps of Uttara, the Murundiya (Muridi-Utaraha seni). Since the epithet 'Muridi' is prefixed to the name '-Utara' (Skt. Uttara), S. Paranavitana believed that Muridi is a derivative of Muruda, which is the same as Murunda in the compound Saka-Murunda that occurs in the Allahabad inscription of Samudragupta. S. Konow (1929: XX), referring to the same inscription argued,S. Konow (1929: XX), referring to the same inscription argued, that murunda is almost certainly a Saka word meaning 'master', 'lord', and he argued that the word murunda has become synonymome with Saka, when applied to royalty. Apart from the coins, beads and intaglios, the contacts between Sri Lanka and the Gandhara region are revealed by other pieces of archaeological evidence from recent excavations at various sites. A fragment of a Gandhara Buddha statute in schisst, still unpublished, was unearthed from the excavations at at Jetavanarama. Most of the identified 'Hellenistic' and Greek-influenced pottery from the citadel of Anuradhapura, and from our recent excavations at Kelaniya appears to be from the Greek East, in other words, somewhere in Northwest India or Bactria.8' ..." Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean, 2002, [by David Parkin, and Ruth Barnes]Himanshu Prabha Ray, Norman Yoffee, Susan Alcock, Tom Dillehay, Stephen Shennan, Carla Sinopoli.

THE MERCHANT LINEAGE AND THE GUILD Page 194: Sri Lanka also provides evidence for niyama or nigama. The Tonigala rock inscription from the Anuradhapura district dated to the third year of the King Srimeghavarna (303-27 CE) records the grant of grain to the Kalahumanakaniyamatana (nigama-sthana), with the stipulation that only the interest is to be used for the maintenance of the monks (Epigraphia Zeylanica III, 1933: 172-98). Another later Brahmi inscription from Labuatabandigala refers to money, i.e. 100 káhápanas being deposited with the Mahatabaka niyama (247-53). Other terms used for guilds are puka or púga and goti (Sanskrit gosthi), the former often being used in association with either a village (Paranavitana 1970, nos. 135, 138; Dias 1991: no. 5) or community, such as that of the Kambojas (Paranavitana 1970, no. 553). There are references to the chief (jete) and sub-chief (anu- jete) of Sidaviya-puka (no. 1198). Literary texts further corroborate these distinctions, for example those between a general trader (vanik) and the setthi, who was possibly a financier, as opposed to the sárthaváha or caravan leader who transported either his own goods or those of other merchants. The sep thi in the Játakas was a man of immense wealth and hence constantly in the retinue of the king. References to rice fields owned by setthis imply that they were both traders and landowners . . Panini refers to traders as vanik (Astádhyáyi, 111.3.52) and makes a distinction between the krayavikrayika (whose main occupation was buying and selling, IV.4.13), the vasnika (who invested his money in business, IV.4.13), the sarnsthanika (a member of a guild, IV.4.72) and the dravyaka (a trader on the outward journey carrying merchandise for sale, Agrawala 1953: 238). In the Amarakosa (11.6.42; 111.9.78), a sárthaváha is described as the leader of merchants who have invested an equal amount of capital and carried on trade with outside markets and are travelling in a caravan. There are several alternative arrangements described in the Játakas by which merchants could purchase or obtain goods. When a ship arrived in a port, merchants converged there to buy the goods and often had to pay money in advance to secure a share in the cargo (Book I: no. 4). Alternatively, a merchant could procure goods by mutual agreement with another living along the border . Once, the Boddhisattva was a wealthy merchant in Varanasi and had as a correspondent a border merchant whom he had never seen. There came a time when this merchant loaded 500 carts with local produce and gave orders to the men in charge to go to the Boddhisattva and barter the wares in his.. Page: 205/206. FOREIGNERS AND TRADE NETWORKS The complexity of economic transactions in the ancient period makes it difficult to determine ethnic identities of trading groups. Another problem is the ambiguity of the literary sources and their inability to distinguish between different ethnic identities, as in the case of allusions to Romans, Arabs, Indians and Ethiopians in Greek and Latin accounts. From the first century BCE to the second century CE, while many of the Arabs of the eastern Mediterranean regions were Roman subjects or Roman citizens, others lived beyond the frontiers of the empire and included groups such as Nabataeans, Palmyrenes, Sabaeans and so on. Early Brahmi inscriptions from Sri Lanka refer to two foreign groups involved in trading activity, i.e. the Damila (Sanskrit Dravida) and the Kabojha (Sanskrit Kamboja). The former figure in an important inscription engraved on the vertical rock face to the north-west of the Abhayagiri monastic complex at Anuradhapura. The inscription records that the terrace belonged to Tamil householders (gahapatikana). The floor of the terrace is on different levels, and the names of the owners are engraved on the rock face below their portion of it, e.g. dameda-samana, dameda-gahapati and navika or mariner. Two other inscriptions refer to a Tamil merchant named Visaka and a householder (Paranavitana 1970: nos. 94, 356, 357). These records are further corroborated by references in the Mahávarimsa, which term the damilas 'assandvikas' or those who brought horses in watercraft (chapter XXI, verses 10-12). It is significant that early Buddhist literary sources from north India refer to the northerners as being involved in trade in horses. The inscriptions referring to the Kabojha or Kambojas are found in ancient Rohana and associate the region with the gamika or village functionary (Paranavitana 1970: nos. 622, 623, 625), there are references to the guild of the Kabojhiyas and its chief (Kabojhiya-maha-pugiyana, no. 553; parumaka or chief of the gota (Sanskrit gostha) Kabojikana, no. 990). The Sihalavatthu, a Pali text of the fourth century, refers to a village of the Kambojas in Rohana. Wheeler identified so-called 'foreign pottery' during his excavations at the site of Arikamedu on the east coast of India (figure 8.5). He used these ceramic finds to endorse not only the nature of trade, i.e., ., Roman, but also the ethnicity of the users and hence suggested an Indo-Roman trading station at the site (Wheeler et al. 1946). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia [Cambridge World Archaeology], 2003, [by: Himanshu Prabha Ray, Norman Yoffee, Susan Alcock, Tom Dillehay, Stephen Shennan, Carla Sinopoli] [The above refernces are quoted here with due gratitude]. Other relevant references on The Kambojas in Sri Lanka are:- History of Ceylone Vol I, Part by Dr S Parnavitana.

- Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, (Chapter: Kambojas in Sri Lanka) Dr J. L. Kamboj.